Chapter 16

Death and Dying

Modified: 2025-07-03 (11:36 AM CDST)

I. Matters of Life and Death (p. 510)

- A. What Is Death?

- 1. Biological definitions of death

- 2. Biological death is a process, not a single event

- 3. Basic bodily process can be maintained by life-supporting machines in people who are in a coma and whose brains have ceased to function

- 4. 1968 Harvard Medical School committee defined criteria for total brain death—irreversible loss of functioning in entire brain (both higher centers of the cerebral cortex that involve thought and lower centers controlling basic life processes like breathing)

- 5. Following four criteria must be met for a person to be judged dead:

- i. Body is totally unresponsive to stimuli

- ii. Failure to move for one hour and failure to breathe for 3 minutes after removed from ventilator

- iii. No reflexes

- iv. Register a flat electroencephalogram (EEG) indicating there is no activity within the brain

- 6. With added precaution, process is repeated after 24 hours and sometimes the coma is reversible coma, such as if it is the result of drug overdose or abnormally low body temperature

- 7. Debate over what parts of the brain must cease to function for a person to be pronounced dead

- 8. Karen Ann Quinlan famous case in 1975

- 9. Lapsed in coma at a party (possibly due to alcohol or drug consumption) and became symbol of controversy over meaning of death

- 10. Unconscious but bodily functions maintained with aid of ventilator or other life-support methods; court granted parents permission to turn off respirator

- 11. Lived in persistent vegetative state being fed by tube for 10 years until she died

- 12. Terri Schiavo’s case led to the question of whether feeding and hydration should be stopped

- 13. Suffered cardiac arrest in 1990 (possibly as a result of an eating disorder) that resulted in irreversible and massive brain damage

- 14. Like Quinlan, Schiavo was not dead according to the Harvard criteria because her brain stem allowed her to breathe, swallow, and undergo sleep-wake cycles

- 15. Husband wanted tube removed but parents fought the decision; courts supported husband, and after long court battle, tube removed and Schiavo died in 2005

- 16. Different positions on issues of when a person is dead

- 17. Harvard position is quite conservative (as are laws of most states)

- 18. More “liberal” criteria for death would be when cerebral cortex is irreversibly dead, even if primitive body functions still maintained by primitive area of brain

- 19. Defining life and death more complicated when it was demonstrated that at least some people in a coma or “vegetative states” may have more awareness than suspected

- 20. Young woman in coma was shown (using brain imaging) to have brain function like a health adult on some tasks, suggesting some degree of consciousness

- 21. Additional support in research on 54 patients in either “vegetative” or “minimally conscious” states found some level of brain response, indicating possible levels of awareness

- B. Life and Death Choices

- 1. Euthanasia—meaning “happy, or good, death,” in which process of death is hastened in person who is suffering

- 2. Active euthanasia or “mercy killing” —deliberately and directly causing death (e.g., administering lethal dose of drug to pain-racked patient in late stages of cancer)

- 3. Passive euthanasia —allowing a terminally ill individual to die of natural causes (e.g., removal of Terri Schiavo’s feeding tube ultimately led to her death)

- 4. Assisted suicide—making available to someone who wishes to die the means by which to do so, includes physician-assisted suicide (e.g., physician writing a prescription for sleeping pills at the request of a terminally ill patient, knowing that the patient will intentionally overdose)

- 5. Societal view of euthanasia and assisted suicide

- 6. Overwhelming support among medical professionals and general public for passive euthanasia

- 7. 70% of the United States adults support doctor’s right to end life of a patient with a terminal illness with patient’s or patient’s family’s consent

- 8. Minority groups less accepting, possibly as the result of less trust in medical establishment or for religious or philosophical reasons

- 9. Active euthanasia still viewed as murder in the United States and most countries

- 10. In most states, legal to withhold extraordinary life-extending treatments from the terminally ill and to “pull the plug” on life-support equipment when that is the wish of the individual or when family member can show that it was the desire of the terminally ill individual

- 11. Living will—a type of advanced directive allowing people to state that they do not want extraordinary medical procedures applied to them

12. Advanced directives can also be written to specify who can make decisions if ill patient is not able to decide whether organs will be donated and other post-death instructions

- 13. Oregon became first state to legalize physician-assisted suicide; individuals who are terminally ill with 6 or fewer months to live can request lethal injection (same request is available in some European countries); few people in Oregon have taken this option; Washington state has followed suit with a similar law

- 14. 40 states have enacted laws against assisted suicide; terminally ill individuals are sometime in no shape to make life-or-death decisions and others speaking for them may not have their best interest at heart

- 15. Right-to-die advocates maintain that people should have a say in how they die while right-to-life advocates say everything possible should be done to maintain life

- C. Social Meanings of Death

- 1. Social and psychological differences in meaning of death

- 2. Societies have evolved some manner of reacting to the universal experience of death (e.g., interpreting its meaning, disposing of the corpse, expressing grief)

- 3. Social meaning of death changed with history

- 4. Middle Ages, people bid farewell to life surrounded by friends and dying with dignity

- 5. Late 19th century in Western society, death taken out of home and put into hospitals (“denial of death”), now have less experience with death

- 6. Right-to-die and death with dignity advocate going back to the old ways (i.e., death out in the open and naturally experienced by families)

- 7. Trending away from funerals with caskets toward cremation

- 8. Experience of dying varies by culture

- 9. Cross-cultural study of 41 cultures found that in 21 there was some kind of practice (e.g., not sharing food, stabbing, driving from their homes) to hasten death in frail, elderly individuals

- 10. Funeral and grieving activities vary by culture (e.g., laughing to weeping; holding parties to avoiding people)

- 11. No single biologically mandated grieving process; grieving may involve holding parties, avoiding people, having sexual orgies, or weeping

- 12. Most cultures have some concept of spiritual immortality

- 13. Differences in social meaning of death seen within North American cultural groups

- 14. Puerto Ricans (especially women) tend to display intense motions, while Japanese Americans often restrain grief expression (smile as to not burden others with their pain)

- 15. Different ethnic and racial mourning practices; Irish Americans often believe that dead deserved a good send off as in a wake with food, drinks, and jokes; African Americans tend to express grief in rowdy celebration; Jews often have a restrained week of mourning for the dead (a shivah) then honor the person at 1-month and 1-year marks

- D. What Kills Us and When?

- 1. Life expectancy at birth—average number of years a newborn is expected to live

- 2. 2010 United States estimate life expectancy at birth is 78 years

- 3. Increased this century in the United States to 76 for white men and 81 for white women

- 4. Female hormones may protect individuals from high blood pressure and heart problems; women less vulnerable to violent deaths and accidents, and the effects of smoking

- 5. Life expectancy for African Americans lower than for European Americans (but the gap is narrowing)

- 6. Historic increase in expectancy from 30 in ancient Rome to 80 in modern affluent societies

- 7. Nations in Africa hit by AIDS, malaria, famine (e.g., Mozambique, Zambia) lag well behind, with life expectancy about 30 years less than those in nations with highest life expectancy (e.g., Japan, Sweden)

- 8. Infancy is most vulnerable period for dying

- 9. Current infant mortality rate in the United States about 7 per 1,000 live births (lower for European Americans; higher for African Americans)

- 10. After infancy, relatively small chance of dying in childhood or adolescence; death rates then climb steadily throughout adulthood

- 11. Leading causes of death change across life

- 12. Infant deaths typically the result of complication of birth or congenital abnormalities

- 13. Leading cause of death in preschool and school-aged children is accidents (e.g., car accidents, poisoning, falls)

- 14. Adolescence time of good health (car accidents, homicide, suicide leading causes of death)

- 15. Young adults killed by accidents, cancer, and some by heart disease

- 16. Age 45 to 65, cancer, heart disease, and chronic diseases

- 17. Genetic endowment and lifestyle may place individual at risk

- 18. Incidences of chronic diseases climb steadily with age

- 19. Age 65 and older, heart disease, cancers, cerebrovascular disease (strokes)

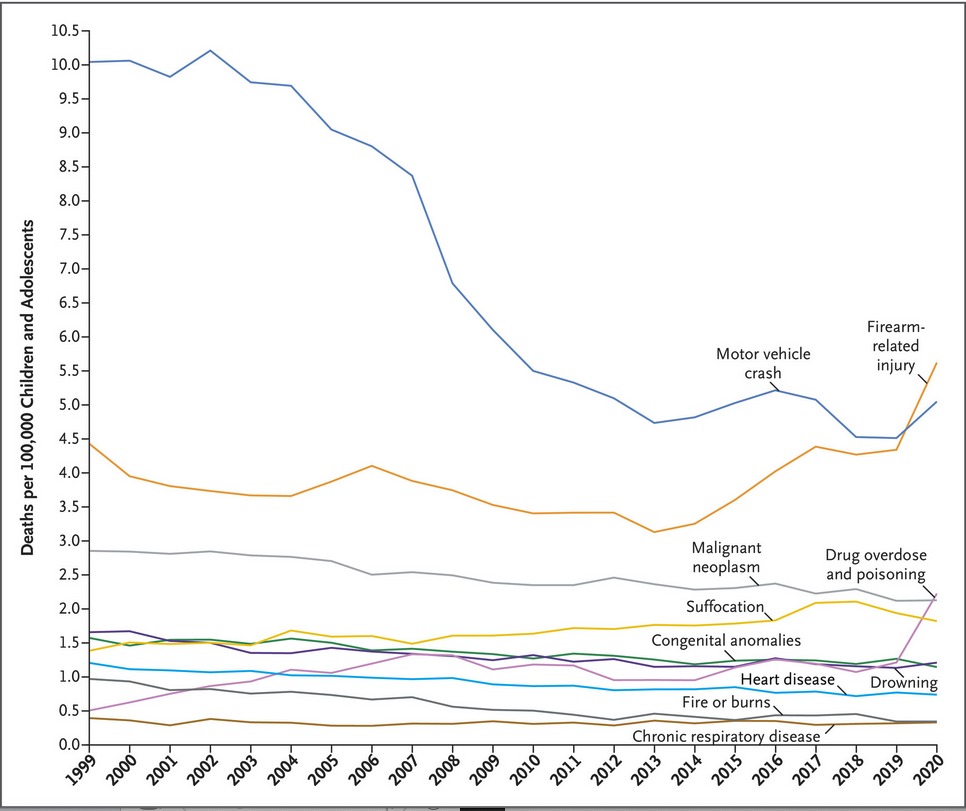

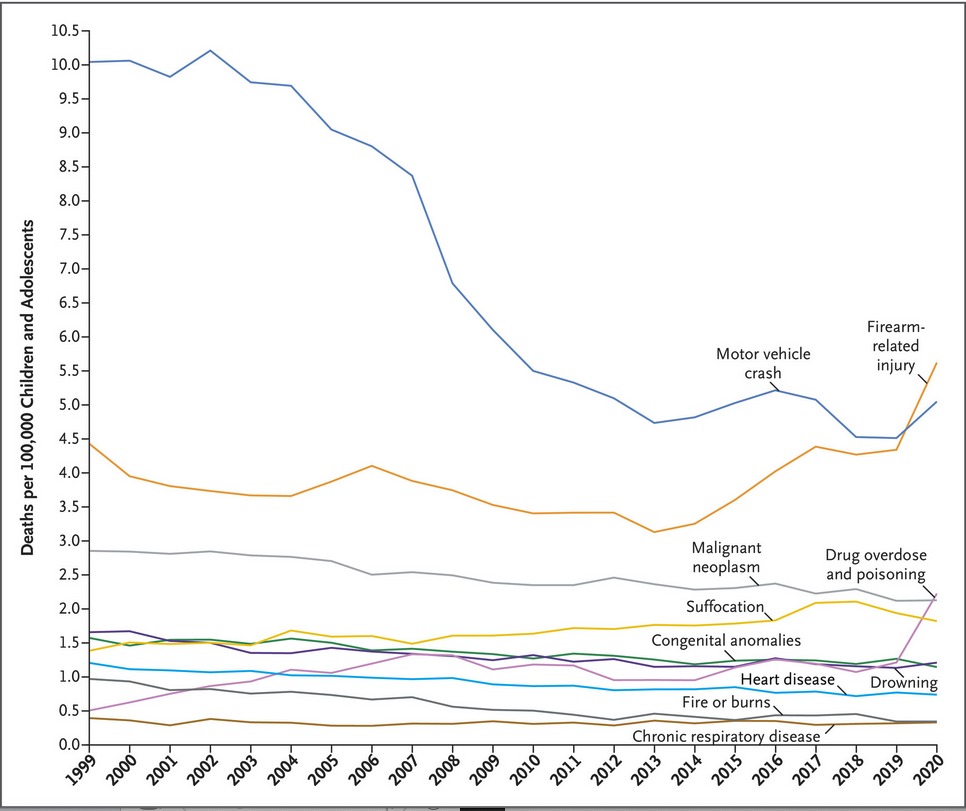

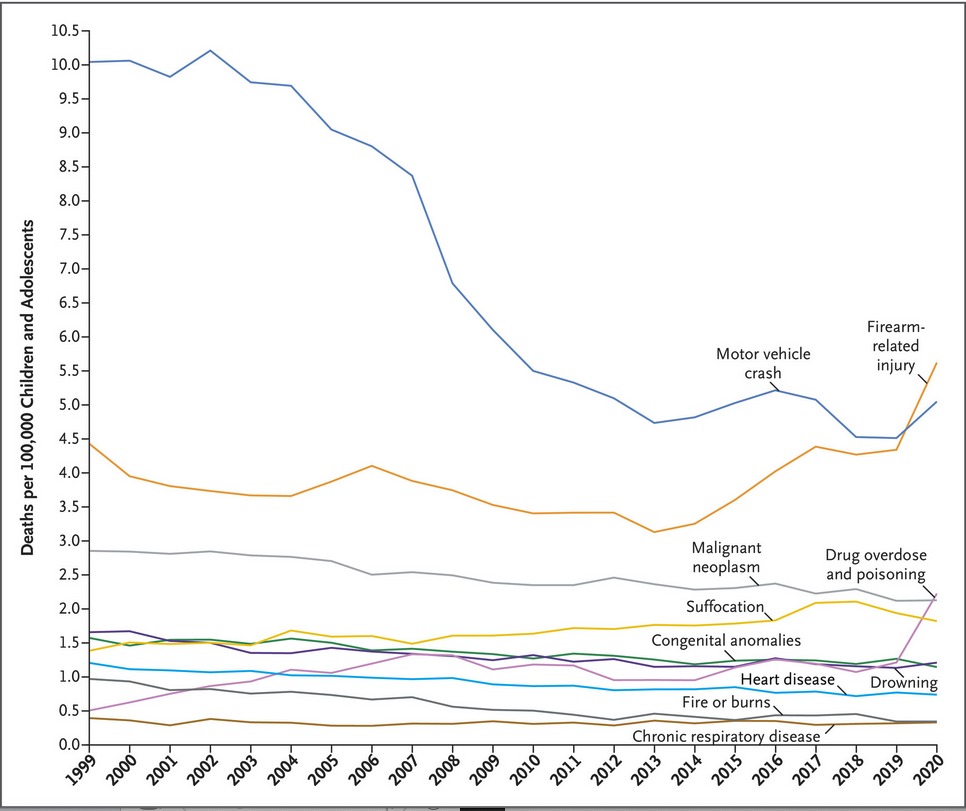

The number one cause of death in US children and adolescents has now become deaths related to firearms, with the rise mostly due to homicides using firearms.

Below is a graph depicting those deaths due to a wide variety of causes (from the New England Journal of Medicine)

- E. Theories of Aging: Why Do We Age and Die?

- 1. Two key categories of aging theories: programmed theories of aging (emphasize systematic, genetic control over aging) and damage theories of aging (more haphazard and due to errors in cells and organ deterioration)

- F. Programmed Theories

- 1. Maximum life span—ceiling number of years anyone within a species can live

- 2. About 120 years in humans (French woman 122 years, quit smoking at 119 when she could not see well enough to light her cigarette)

- 3. Maximum life span not increased much in past century, despite the fact that average life expectancy increasing by almost 30 years

- 4. Humans comparatively long-lived (maximum life: mouse 31/2 years, Galapagos tortoise 150 years)

- 5. Fact that different species have different life spans suggests a species-wide genetic influence

- 6. Genetic makeup and environment combine to determine length of life

- 7. Genetic variation accounts for more than 50% of variance in the ability to stay free of major chronic diseases at age 70 or older

- 8. Average longevity of parents and grandparents good estimate of one’s longevity

- 9. Many genes likely involved in aging process through regulation of cell division

- 10. Genes that become less active with age in normal adults are inactive in children with progeria—premature aging disorder caused by a spontaneous (rather than inherited) mutation in a single gene

- 11. Babies with progeria appear normal at first but age prematurely and die on the average in their teens (often due to heart disease or stroke)

- 12. “Evolutionary puzzle” concerning genes and life span

- 13. Genes that act late in life to extend life will not be selected for during the evolutionary process

- 14. Genes that proved adaptive to ancestors in early life but have negative outcomes could become common in a species over time because they would be selected for due to their positive impact on reproduction

- 15. A gene that limits creation of new cells through cell division could protect against the proliferation of cancer cells in early life but also contributes to cell aging later in life

- 16. Possibility of “aging clock” in every cell

- 17. Hayflick limit—human cells can divide a limited number of times (50 times plus or minus 10)

- 18. Capacity for cell reproduction related to differences in maximum life span by species (mouse 14 to 28; tortoise 90 to 125 divisions)

- 19. May be due to shortening of telomeres

- 20. Telomeres—stretches of DNA that form the tips of chromosomes and shorten until cells cease to replicate causing them to malfunction and die (telomere is a yardstick of biological aging)

- 21. Chronic stress may lead to shortening of telomeres (is concrete emphasis that stress speeds cellular aging)

- 22. Lack of exercise, smoking, obesity, and low SES (all risk factors for aging) are also associated with short telomeres

- 23. Other programmed theories

- 24. Genetically driven systematic changes in neuroendocrine system and immune system

- 25. Possible that hypothalamus serves as an aging clock, systematically altering levels of hormones and brain chemicals in later life so that we die

- 26. Possible that aging is related to genetically governed changes in the immune system associated with the shortening of telomeres; may decrease immune system’s ability to defend against life-threatening infections, may cause it to mistake normal cells for invaders (as in autoimmune diseases) and contribute to inflammation and disease

- G. Damage Theories

- 1. Damage theories view aging in terms of an accumulation of haphazard or random damage to cells and organs over time (wear and tear)

- 2. Early cells replicate faithfully, late cells show random damage

- 3. Biological aging is about random change rather than genetically programmed change

- 4. Free radicals—toxic and chemically unstable byproducts of everyday metabolism, or the everyday chemical reactions in cells such as those involved in breaking down food

- 5. Free radicals produced when oxygen reacts with certain molecules within cells; they have extra or “free” electrons that react with other molecules to produce substances that damage cell and its DNA

- 6. Over time, genetic damage becomes more chaotic and the body cannot repair the damage, results in cells functioning improperly and eventual death of the organism

- 7. “Age spots” on skin are visible examples of free radical damage

- 8. Free radicals implicated in major disease common with aging (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, cancer)

- 9. Some question the impact of free radicals on aging as there is no clear relationship between metabolic rate and longevity

- H. Nature and Nurture Conspiring

- 1. Programmed theories view aging and dying as part of natures’ plan

- 2. Maximum life span, Hayflick’s limit, changes in gene activity with aging suggest that aging and dying are genetically controlled

- 3. Damage theories hold that we succumb to haphazard destructive processes

- 4. Neither programmed nor damage theories are the explanation of aging and dying

- 5. Aging is result of interaction between biological and environmental factors

- 6. Extending life

- 7. Life spans of 200 to 600 years unlikely, but average age of death could move toward 112, and individuals at that age may function like modern 78-year-olds

- 8. Stem cells may allow us to replace aging cell or modify aging processes

- 9. The enzyme telomerase can be used to prevent telomerase from shortening and this will keep the cell replicating and working longer (downside is that it make cancer cells divide more rapidly)

- 10. Antioxidants

- 11. New focus on preventing damage from free radicals using antioxidants like vitamins E and C that prevent oxygen from combining with other molecules to produce more free radicals

- 12. Antioxidants may increase longevity (although not for a long time) by inhibiting free radical activity; caution is advised as exceptionally high levels of vitamin E may shorten rather than lengthen life

- 13. Caloric restriction

- 14. Most successful life-extending technique is caloric restriction—a highly nutritious but severely restrictive diet representing a 30–40% cut in normal caloric intake

- 15. Lab tests using caloric restriction on primates and rats suggest that it extends both the average longevity and maximum life span of a species and it can delay the progression of many age-related diseases

- 16. 40% reduction in daily calories leads to a 40% decrease in body weight, a 40% increase in average longevity, and a 49% increase in species maximum life span

- 17. Caloric restriction works by reducing the number of free radicals and other toxic products of metabolism; it also may alter gene activity and trigger the release of hormones that slow metabolism and protect cells against oxidative damage

- 18. Long-lived humans are rarely obese

- 19. Individuals who lived in Biosphere II and who consumed about 1,800 calories a day lost 15–20% of their body weight; they experienced significant improvement in several physiological indicators, but the impact disappeared once they went back to normal diets

- 20. Experimenting with self-starvation is unwise

- 21. Some worry about the social consequences if average longevity were pushed to 100 to 120 years due to high healthcare costs, overpopulation, bankruptcy of Social Security system

II. The Experience of Death (p. 517)

- A. Perspectives on Dying

- 1. Kübler-Ross’s Stages of Dying

- a. Book On Death and Dying in 1969 revolutionized the care of dying people

- b. Based on interviews with terminally ill patients, Kübler-Ross detected a common set of emotions in terminally ill individuals and thought that similar reactions might occur in response to any major loss

- c. Her five “stages of dying” of the terminally ill

- d. Denial and isolation—“No, it can’t be”

e. Common first response

- f. Denial—mechanism for keeping anxiety-provoking thoughts from conscious awareness

g. Individual may insist that the diagnosis is wrong or may be convinced that he or she will beat the odds and recover

- h. Care provider and family member often engage in their own denial

- i. Anger— “Why me?”

- j. Rage or resentment often directed at doctors or family members

- k. Family and friends need to be sensitive to this reaction

- l. Bargaining— “Okay, me, but please…”

- m. Beg with God, medical staff, others for cure, more time, less pain, or provisions for children

- n. Depression

- o. Grief focuses on losses that have already occurred, loss of ability to function, and losses to come

- p. Acceptance

- q. Accept the inevitability of death in a calm and peaceful manner

- r. Almost devoid of feelings

- s. Hope, a sixth response that runs throughout the other five responses

- 2. Problems with Kübler-Ross’s Theory

- a. Kübler-Ross deserves credit for sensitizing society to emotional needs of the dying

- b. Main criticism—dying process simply not stage-like

- c. Many do not display all the stages

- d. Death responses seldom unfold in a standard order

- e. Overzealous physicians often try to push patients to die in the correct “stage” order

- f. Shneidman argues that dying patients experience complex interplay of emotions alternating between denial and acceptance

- g. Additional reactions include disbelief, terror, bewilderment, and rage

- h. Dying people experience unpredictable emotional changes rather than distinct stages of dying

- i. Second criticism—little attention on how responses or trajectory of responses are shaped by specific illnesses and events

- j. Pattern different for those with slow, steady progression toward death versus more erratic pattern

- k. Third criticism—overlooks influences of personality on how a person experiences dying

- l. People who previously have faced life’s problems directly and effectively and maintain good interpersonal relationships tend to be less angry and less depressed when dying

- m. Personality traits, coping abilities prior to death, and social competence may cause some to be bitter to the end, others to be crushed by despair, and others to display incredible strength

- 3. Perspective on Bereavement

- a. Key terms

- b. Bereavement—state of loss

- c. Grief—emotional response to loss

- d. Mourning – culturally defined ways of expressing grief

- e. Anticipatory grief—grieve for a terminally ill person prior to death (does not eliminate grief felt after actual death)

- 4. Parkes/Bowlby Attachment Model

- a. Conceptualizing grieving in context of attachment theory (influenced by Bowlby’s ethological theory of attachment)

- b. Parkes, “loss and love are two sides of the same coin”

- c. Model of bereavement includes four predominant reactions that overlap considerably and as such should not be viewed as clear-cut stages

- d. Numbness—sense of unreality and shock experienced during first few hours or days following death; bereaved struggling to defend against weight of loss

- e. Yearning —pangs or waves of grief coming from 5 to 14 days after death as form of separation anxiety; includes uncontrollable weeping, physical aches and pains, and pining and yearning for the loved one (a longing to be reunited); signs of separation anxiety—distress at being parted from object of attachment; common reactions include anger, guilt, feelings of irritability, and intense rage at loved one for dying

- f. Disorganization and despair —passage of time, yearning and grieving less frequent and less intense, predominant emotions include depression, despair, and apathy

- g. Reorganization —begin to invest less energy in grief for deceased and transition into life without person; if married, begin to make the transition to being without spouse and engage in new activities and possibly new relationships

- h. Research shows reaction peaks occur at times predicted by theory, however, acceptance was the strongest response at all stages, yearning was the second strongest response, and remaining responses relatively weak; worst of grieving process is over in first 6 months after loss

- 5. The Dual-Process Model of Bereavement

- a. Pattern of grief “messier” and more individualized than Parkes/Bowlby phases suggest

- b. Dual-process model of bereavement—bereaved oscillate between coping and emotional blow of the loss

- c. Loss-oriented coping—dealing with one’s emotions and reconciling to loss

- d. Restoration-oriented coping—focus on managing daily living and mastering new roles

- e. Both loss- and restoration-oriented issues need to be confronted but they also need to be avoided at times

- f. Over time, tend to shift from loss-oriented to restoration-oriented coping

- g. Bereavement is complex and multidimensional process involving many ever-shifting emotions that vary greatly from one person to another and that often takes a long time

- h. Modest disruptions in cognitive, emotional, physical, and interpersonal functions common (last for a year or so)

- i. Sympathetic toward bereaved immediately after death but grow quickly weary of someone who is depressed, irritable, or preoccupied (think the person needs to cheer up and get on with life)

- j. Must understand that reactions to bereavement might linger

III. The Infant (p. 521)

- 1. Notion of objects being and “missing” to begin to understand death

- 2. First form global category of things may be “all gone” (i.e., dead) and later divide it into subcategories that includes “dead”

- 3. Disappearance of the loved one is the most direct evidence of death for infants, and at this level Bowlby’s attachment theory helpful

- 4. Distress similar to symptoms of separation anxiety (e.g., protest loss by crying, yearning, and searching)

- 5. Separation from attachment figure same reaction as bereaved adults

- 6. Initial vigorous protest phase, yearning, and searching for loved one

- 7. After hours or days of protest and unsuccessful searching, infants begin to show despair—depression-like symptoms (e.g., lose hope, end search, become apathetic and sad)

- 8. Eventually enter detachment phase—renewed interest in toys and companions

- 9. Complete recovery if infant can rely on existing attachment figure

IV. The Child (p. 522)

- A. Grasping the Concept of Death

- 1. Young children highly curious about death, yet beliefs considerably different than adults

- 2. Children must acquire a “mature” understanding of death that is characterized by:

- 3. Finality—end of movement, thought, sensations, and life

- 4. Irreversibility—cannot be undone

- 5. Universality—inevitable

- 6. Biological causality—result of internal processes (that may be caused by external forces)

- 7. Preschool children

- 8. Understand the universality of death

- 9. Believe the dead retain some life functions, are living under altered circumstances, but still have hunger, wishes, and love their moms

- 10. View death as reversible (i.e., liken to sleep or a trip, with right medical care or magic can come back)

- 11. Death viewed as being caused by external agent (e.g., eating a dirty bug) not biological causes

- 12. School-age children (5 to 7 years) have more advanced conceptualization of death

- 13. Understand finality, irreversibility, and universality

- 14. Understanding functions of the body helps preschoolers grasp concept of death

- 15. Infer that death is opposite of life

- 16. Do not completely understand biological causality of death (e.g., heart stops) until around age 10

- 17. Understanding of death depends on level of cognitive development, culture, and life experiences

- 18. Breakthrough in death understanding tied to transition from preoperational to concrete operational stage and IQ

- 19. Understanding of death influenced by cultural factors

- 20. Christian and Jewish children in Israel who are taught Western concept of death have more “mature” understanding

- 21. In cultures promoting idea of reincarnation, death often not viewed as irreversible

- 22. Own life experience (especially a life-threatening illness in childhood) can impact thoughts and behaviors concerning death and dying

- 23. Adult use of euphemisms (e.g., “grandma has gone to live with God”) can confuse and frighten children

- 24. Simple and honest answers to children’s questions about death are best

- B. The Dying Child

- 1. Typically more aware that they are dying than adults realize

- 2. Over time, preschoolers with leukemia understand that death irreversible

- 3. Despite secretiveness, terminally ill children notice change in their treatment and pay close attention to what is happening to other children with the same disease

- 4. Children stop talking about long-term future including celebration of holidays

- 5. Terminally ill children often not “models of bravery” that some suppose them to be, but rather experience many emotions of dying adults

- 6. May demonstrate fear in play behavior through tantrums

- 7. Seek normalcy in school and athletic activities so that they do not feel inadequate with peers

- 8. Terminally ill children need love and support of others

- 9. Benefit from strong sense that parents care for them and from opportunity to talk about their feelings

- C. The Bereaved Child

- 1. Children do grieve, however, their grief is expressed differently than an adult’s grief

- 2. Lack some of the coping skills that adults have

- 3. Particularly vulnerable to long-term negative effects of bereavement

- 4. Common reactions of bereaved child

- 5. Often misbehave or strike out at others

- 6. Ask endless questions about death and deceased

- 7. Experience anxiety concerning separation, including worry that other family members might die

- 8. Some children go about activities as if nothing happened (denying loss)

- 9. Lack of cognitive abilities impact coping skills, and they may not understand what is going on

- 10. Young children mainly have behavioral or action coping strategies (e.g., put picture of deceased mom by pillow at night and return to frame during the day); older children able to use cognitive coping strategies like conjuring up mental representations of their lost parents

- 11. Common grief symptoms vary from person to person and by age

- 12. For preschoolers, common reactions include daily routine problems (e.g., sleeping, eating), negative moods, dependency, and temper tantrums

- 13. For older children, there is more direct expression of sadness, anger, fear, and physical ailments

- 14. Some carry negative adjustment pattern into adolescence and adulthood (e.g., depression, insecurity in attachments)

- 15. Most bereaved children with effective coping skills and solid social supports adjust well

- 16. Best adjustment when the receive good parenting, if caregivers communicate that they will be loved and cared for, and if they have the opportunity to talk about and share their grief

V. The Adolescent (p. 526)

- A. Advanced Understandings of Death

- 1. Typically understand death as irreversible cessation of biological processes and can think abstractly about death

- 2. Cognitive advancement (i.e., achievement of formal-operational stage thought) leads to ability to ponder hypothetical afterlife

- 3. Like younger children, may believe that knowing, believing, and feeling continue after bodily functions have ceased

- B. Experiences with Death

- 1. Adolescent reaction to dying reflects advanced developmental capacities

- 2. Worry how illness might affect appearance (e.g., hair loss, amputation)

- 3. Want to be accepted by peers and may feel like “freak”

- 4. Eager to be more autonomous (distressed if they have to be dependent on parent or medical personnel)

- 5. May be angry or bitter at having dreams snatched from them

- 6. Reaction to loss of friend or family member reflect themes of adolescent period

- 7. May carry on internal dialogue with dead parent

- 8. Often devastated if loss involves a close friend

- 9. 32% of teens with friend who committed suicide experienced clinical depression during the month after the suicide

- 10. Grief over loss of family member may be taken more seriously, and parents, teachers, and others may not appreciate how much the teen is hurting

- 11. Adolescents are sometimes reluctant to express grief for fear of seeming abnormal or losing control

- 12. Adolescents who yearn for dead parent may feel like they will be sucked back into dependency of childhood

VI. The Adult (p. 527)

- A. Death in the Family Context

- 1. The Loss of a Spouse or Partner

- a. Marital relationship is central one for most adults, and loss of marital partner or other romantic attachment figure can mean a great deal

- b. Precipitates other changes (e.g., changes in residence, job status)

- c. Bereaved must redefine roles and identities

- d. Women will likely see substantial decline in income

- e. Widow and widower reactions

- f. Widows and widowers show overlapping phases of numbness, yearning, despair, and reorganization

- g. Increased risk for illness and physical symptoms (e.g., loss of appetite)

- h. Tend to overindulge in alcohol, tranquilizers, and cigarettes

- i. Cognitive functions and decision-making may be impaired

- j. Emotional problems like loneliness and anxiety are common

- k. Most bereaved partners do not become clinically depressed but display increased symptoms of depression

- l. Modest level of disruption that tends to last for a year, followed by less severe but recurring grief reactions for several years

- m. Great variation in individual pattern of response to loss

- n. Five most prevalent patterns of widows and widowers adjustment:

- i. A resilience pattern—distress at low levels all along

- ii. Common grief—heightened then diminished distress after loss

- iii. Chronic grief—loss brings distress and distress lingers

- iv. Chronic depression—individuals depressed before loss remain so after

- v. Depressed-improved pattern—depressed before loss, less depressed after (relieved of stress of coping with unhappy marriage or spouse illness)

- o. Biggest surprise is that the resilience pattern is the most common response

- p. Resilient grievers experienced some emotional pangs, but more comforted by positive thoughts of the deceased

- q. No signs of defensive denial or avoiding pain in this group

- r. Those with symptoms of depression tend to have been depressed before the loss and tend to remain depressed for years later

- s. Those who became depressed in response to the death often recover within a year or two

- t. Depressed-improved individuals may have been experiencing caregiver burden before the death and relief afterwards

- u. Do partners of gay men who die of AIDS experience similar patterns of bereavement?

- v. Half of the bereaved showed resilience (whether they were HIV positive themselves did not seem to matter)

- w. Disenfranchised grief—grief that is not recognized or appreciated by other people and therefore may not result in much support—sometimes experienced by gays and lesbians who lose partners

- x. Losses of ex-spouse, extramarital lovers, foster children, fetuses, and pets can lead to disenfranchised grief

- y. Disenfranchised grief common when loss is not recognized or acknowledged, bereaved is excluded from mourning activities, and when loss is stigmatized (e.g., suicide)

- z. Overall, most bereaved individuals experiencing significant loss begin to show signs of recovery after a year or so

- a. A minority of bereaved may experience complicated grief—less common form involving prolonged or intense grief that impairs functioning

- b. Often diagnosed with depression, or if death was traumatic, with posttraumatic stress disorder; may see this as a distinct condition that some believe should be considered a distinct disorder from depression of PTSD

- 2. The Loss of a Child

- a. No loss seems more difficult for an adult; even with forewarning, experienced as unexpected, untimely, and unjust

- b. Sense of failed role as parent

- c. Failure to find meaning in the death even long after the death; one study of children who died of an accident, suicide, or homicide found that only 57% of parents had found meaning in the death after 5 years

- d. Age of child has little impact (severe grief may occur for a miscarriage, especially for mothers)

- e. Death alters family system

- f. Effects on marriage—strains relationships; strain worse in marriages shaky before death

- g. Increased risk for marital problems and divorce, although most couples stay together and become closer

- h. Parents who focus on restorative-oriented coping and less on loss-oriented coping may fare better

- i. Effects on siblings—may feel neglected by parents, anxious about own health, guilty about feeling of sibling rivalry, pressure to replace lost child in their parent’s eye

- j. Effects on grandparents—a “double whammy” involving guilt over out surviving their grandchild and helplessness to protect adult child from pain

- 3. The Loss of a Parent

- a. Not as difficult an adjustment as death of spouse or child, as it commonly occurs in middle age when individuals better prepared to deal with loss

- b. Can be turning point affecting identity and relationships with many family members

- c. Adult children may feel vulnerable and alone

- d. Guilt about not doing enough for parent is common

- B. The Grief Work Perspective and Challenges to It

- 1. Grief work perspective—in order to cope with death, the bereaved must confront loss (model grew out of Freudian psychoanalytic theory)

- 2. Chronic grief (long-lasting and intense) and absence, inhibition, or delay of grief (lack of common reactions) both associated by Freudians with pathological or complicated grief

- 3. Grief-work perspective under attack as many question the assumption that there is a “right way” to grieve, that bereaved people must experience and work through intense grief to recover, and that they must sever their bonds with the deceased in order to move on with their lives

- 4. Cross-cultural research showing wide variety of successful grief patterns (e.g., Egyptian mother conforms to norms by sitting alone and mute for years after child’s death, Balinese mother is following her cultural norms if she is seemingly cheerful after her child’s death)

- 5. Little support for assumption that the bereaved individual must confront loss and experience painful emotions to cope successfully; those who are most resilient display little distress at any point in bereavement; too much grief work might result in effect like ruminative coping and prolong psychological distress rather than relieve it

- 6. Do not need to completely break from the deceased but rather revise internal working model of self/others to compensate for loss; continuing bonds—indefinite attachment driven by reminiscing and sharing of memories of deceased tend to result in feelings of comfort

- 7. Some forms of continuing attachment healthier than others

- 8. Sharing fond memories of deceased and feeling that loved one is watching over and guiding experience means less distress

- 9. Use of deceased’s possessions for comfort led to higher levels of distress

- 10. Continuing bonds helpful when they are in the form of internal memories of the deceased that provide a secure base for becoming more independent but not when they involve hallucination and illusions that reflect a continuing effort to reunite with the deceased; cultural influences may impact adjustment

- 11. Flaws in traditional grief-work perspective

- 12. Norms for expressing grief vary by culture—no one normal and effective way to grieve

- 13. Little evidence that bereaved must do intense “grief work”

- 14. People do not need to sever attachments to the deceased to adjust to loss and may benefit from some continuing bonds

- 15. Most do not experience pathological grief symptoms; more common to experience positive emotions along with negative emotions

- C. Who Copes and Who Succumbs?

- 1. Personal resources influence an individual’s ability to cope with bereavement

- 2. Attachment style is an important resource (or liability)

- 3. Secure attachment associated with coping relatively well

- 4. Resistant or preoccupied styles of attachment associated with over dependence and extreme displays of chronic grief and anxiety following a loss, ruminating about the loss, and clinging to the loved one rather than revising the attachment bond

- 5. Avoidant or dismissing attachments linked to greater difficulty in expressing emotions and seeking comfort, may disengage from or devalue the person lost

- 6. Disorganized attachment style associated with being especially unequipped to cope; may turn inward and harm self or abuse alcohol

- 7. Personality and coping style

- 8. Those with a low sense of self-esteem tend to have difficulty coping with loss

- 9. Depression and other chronic psychological disorders may increase difficulty in dealing with loss

- 10. Optimistic individuals find positive ways to interpret loss and tend to use active and effective coping strategies

- 11. Loss of someone with whom you have a close relationship (e.g., spouse) hits people hardest

- 12. Cause of death influences bereavement; senseless or violent deaths are worse (e.g., death of child)

- 13. Sudden death is not necessarily harder to cope with because the advantages of being forewarned are offset by the stress of caring for the dying loved one

- 14. Presence of strong social support systems and life stressors can positively impact grief reaction

- 15. Social support (e.g., parents, siblings, friends) helps at all ages

- 16. Simple ways to be supportive include indicating sorrow about the loss, asking how things are going, and allowing bereaved to express feelings of pain is helpful

- 17. Additional stressors hurt recovery

- 18. Widow and widowers more troubled if they must single-handedly care for a child, find job, or move

- D. Posttraumatic Growth

- 1. Although painful, grief has potential to foster growth in self, religiosity, family relationships, and appreciation of life

- 2. Many widows may master new skills, become more independent, and emerge with new identities and higher self-esteem

- 3. From tragedy sometimes comes meaning

VII. Taking the Sting Out of Death (p. 535)

- A. For the Dying

- 1. Hospice option—program to support dying individuals

- 2. Philosophy of “care” rather than “cure” founded at St. Christopher’s Hospital in London and quickly spread to North America

- 3. Hospice care may take place at care facility or at home

- 4. Hospice care is part of a larger palliative care movement—emphasis of care aimed not at curing disease or prolonging life but at meeting physical, psychological, and spiritual needs of patients with incurable illness [mention TXK hospice, how government pays]

- 5. Key features of hospice care (whether at home or in a facility)

- 6. Dying person and family the decision-makers (not medical care “experts”)

- 7. Deemphasis on attempting to cure disease or prolonging life (but death not hastened)

- 8. Emphasis on pain control

- 9. Emphasis on comfort of setting being as normal as possible (preferable in home or homelike facility)

- 10. Bereavement counseling available to entire family

- 11. Impact of hospice care different from medical care

- 12. Less interest in physician-assisted suicide

- 13. More emotional support (something often lacking in home healthcare agencies, nursing homes, and hospitals)

- 14. Fewer medical interventions

- 15. Fewer symptoms of family grief from spouses, partners, parents, and relatives of dying individual

- 16. Hospice not for everyone, but is death with dignity that’s free of pain and while surrounded by others; good option for some

- 17. Next challenge of hospice philosophy involves children dying of cancer with uncontrolled pain

I must report that I am now well aware of in-home and resident hospice care. My late father-in-law passed in April 2023 at a hospice in Texarkana, TX, he was a month short of his 87th birthday. Before he needed to be in residence there he was using home hospice. His wife had passed in August 2021 at the age of 79. He discovered her lying on the living room floor, having trouble breathing and unable to speak. He called 911 but she died shortly afterwards. At that point he was barely mobile; he needed to use a walker and could not walk very far because of a long-term heart condition. From that point on he gradually declined. After he was unable to get up out of his lounge chair, and thus take care of his daily needs, he entered home hospice. He wanted to avoid entering a nursing home.

He hired a 24 hour care service. They had someone with him at the house all day and all night. In addition, hospice nurses called on him a couple of days a week to check his condition. His care workers took care of all of his daily needs. His Medicaid covered his hospice expenses. They provided a hospital bed (installed in the living room) and a hoist. Later, they brought in an oxygen tank to help his breathing. At around the sixth month mark, however, he proved too hard to care for. He could no longer control his elimination of wastes, had become much more forgetful, and had intentionally thrown himself from his bed.

He was then moved to a hospice in town. I was struck by the level of near luxury of the single patient rooms. Each had a bathroom and a porch (not that many of the residents could use either). The staff was extremely professional and took care of all of his needs. We in the family could visit, and did so often. Death came slowly but predictably. By the end, all he could do was breathe raggedly. He no longer took notice of his surroundings nor did he attempt to speak or otherwise communicate. The staff knew when the end was coming and notified the family.

I spoke to one of the nurses. She reported that eight residents had died that week. That made me wonder what kind of psychological toll that took on the staff. When he was still at home in hospice, he and his staff bonded with each other and became quite attached. They too must undergo a psychological toll, perhaps greater than that of the nurses at the hospice building. They only "knew" him for a short while. His home staff had lived together for months.

His death and dying was a long process that gradually developed over years. The family is still grieving, of course, and is doing the many duties that follow a death.

- 1. Most bereaved individuals do not need psychological intervention, but options are available

- 2. At-risk individuals (with depression, other psychological disorders, or lacking support) may benefit from counseling designed to reduce depression

- 3. Family therapies most effective

- 4. Family Bereavement Program — for children and adolescents (and surviving parent) who had lost a parent

- 5. Many specific support programs like Companionate Friend, Partners without Parents, and They Help Each Other Spiritually (THEOS) offer bereaved advice on

- a variety of issues from finances to emotional support

- 6. Participation in support groups tends to be beneficial (e.g., less depression, less use of medication, greater sense of well-being); other bereaved individuals may be helpful because they understand what the individual is going through (i.e., are in the “same boat”)

- C. Taking Our Leave

- 1. Reminders of these themes echoed throughout book

- 2. Nature and nurture truly interact in development (environment and biology interact reciprocally)

- 3. We are whole people throughout the life span (advances in one area have implications for other areas)

- 4. Development proceeds in multiple directions

- 5. There is both continuity and discontinuity in development

- 6. There is much plasticity in development

- 7. We are individuals, becoming even more diverse with age

- 8. We develop in a culture and historical context

- 9. We are active in our own development

- 10. Development is a lifelong process

- 11. Development is best viewed from a multiple perspective

Back to Main Page

Back to TAMUT Start Here Page